Flight from England to Umtali (Rhodesia Herald) (By A.H. Elton)

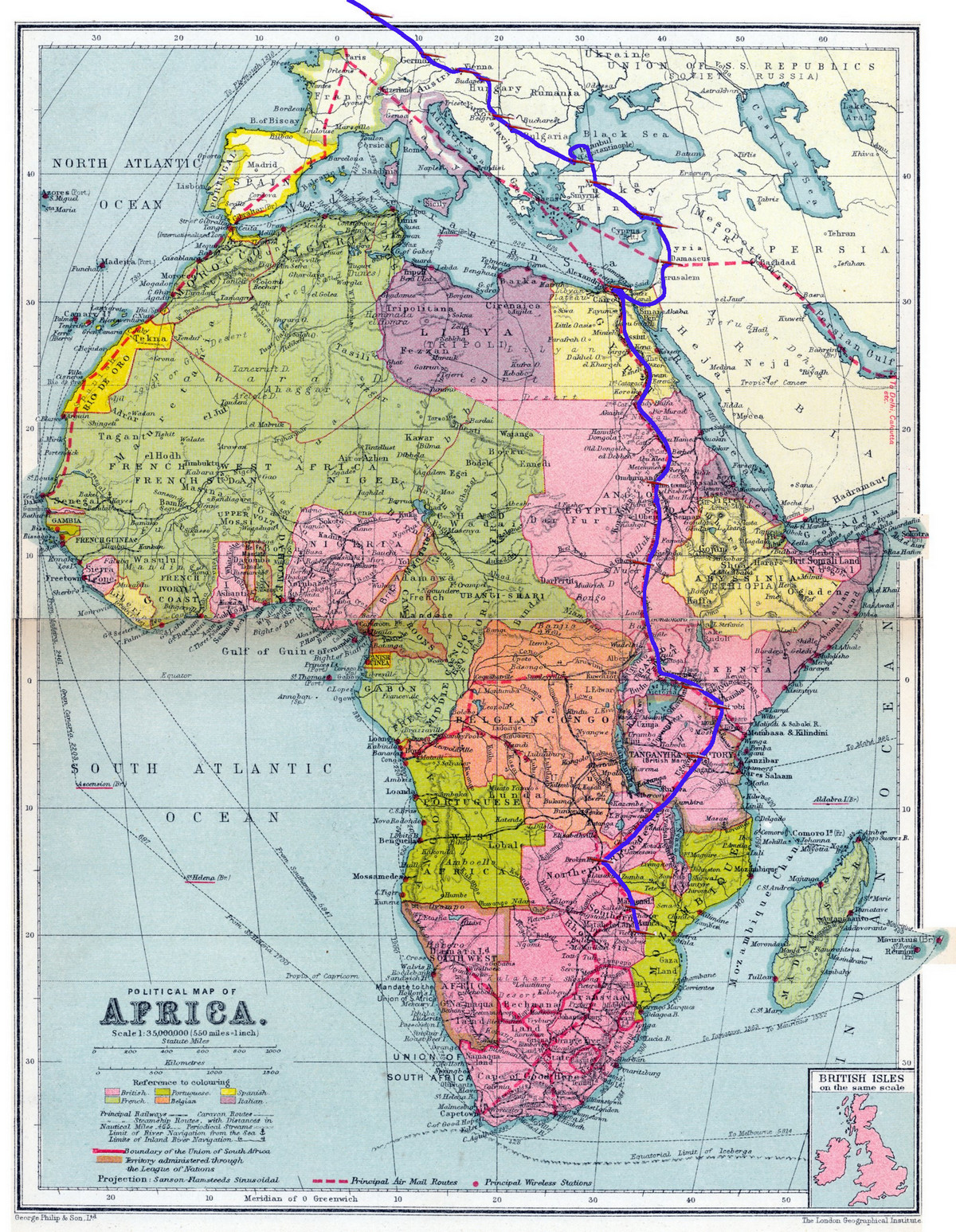

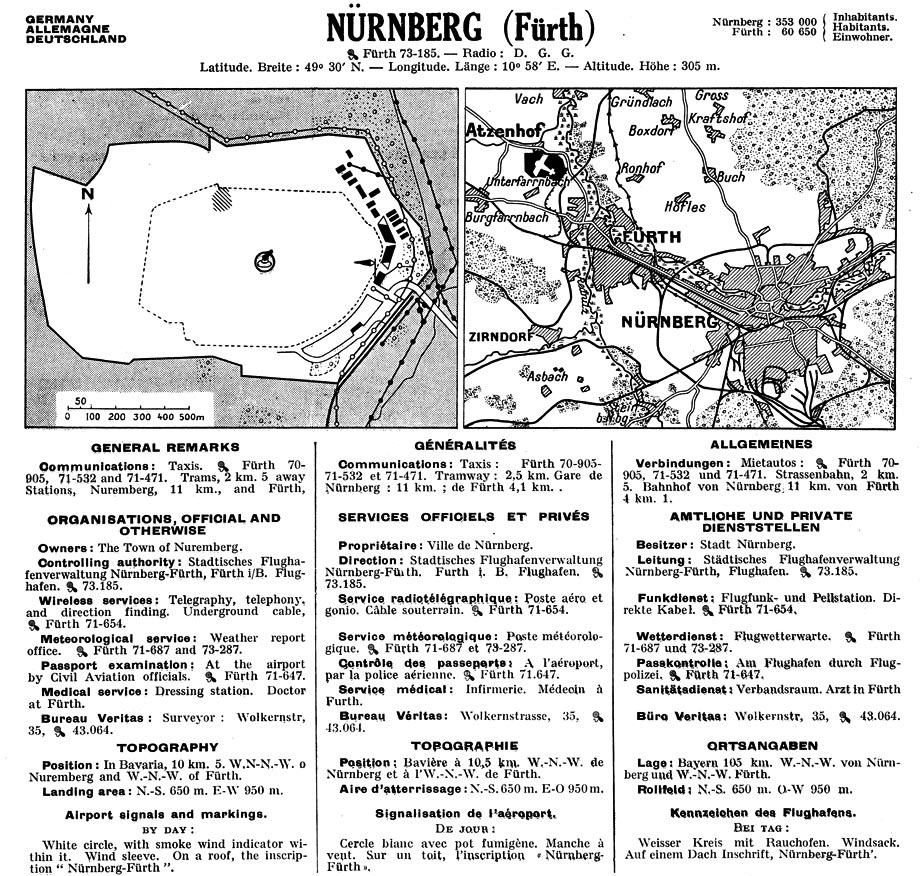

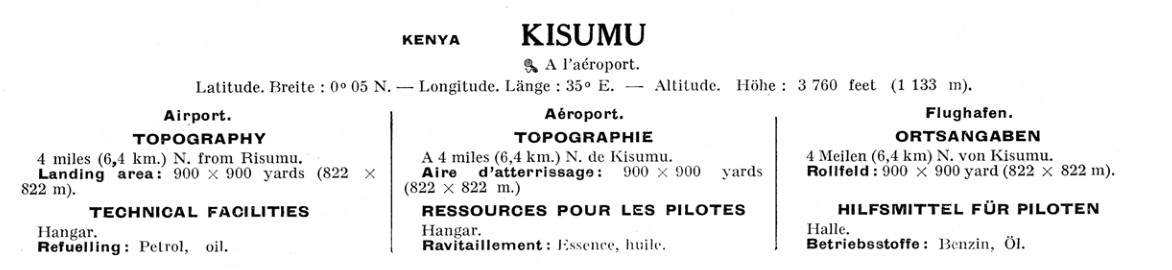

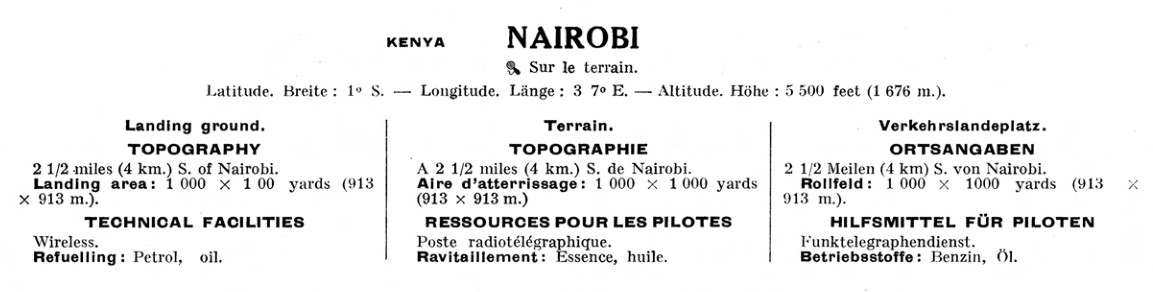

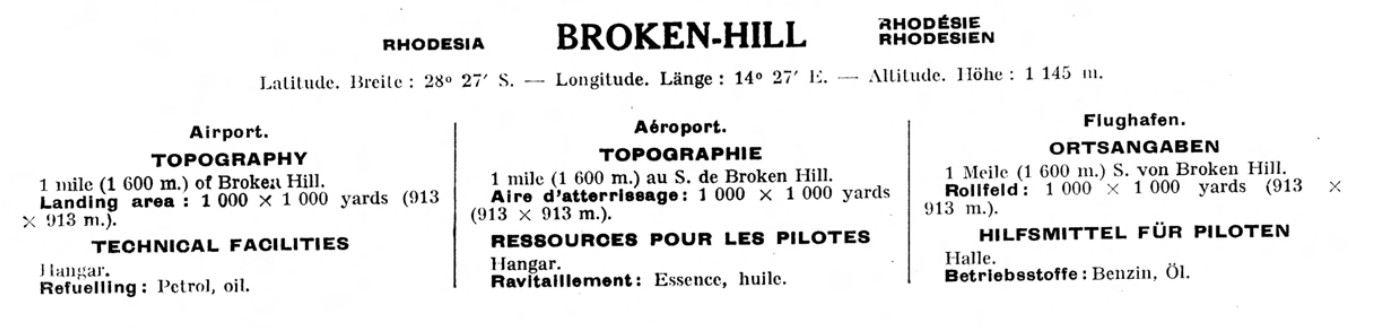

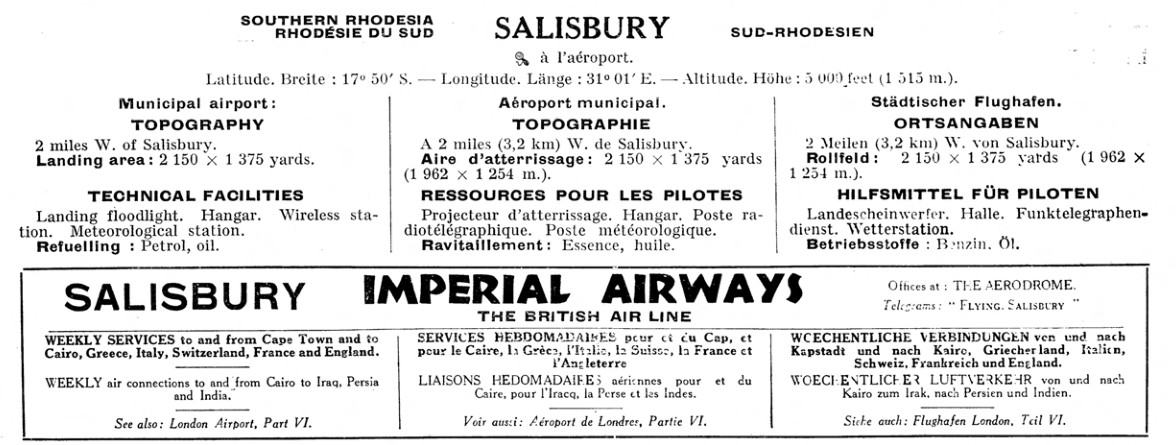

The following article has been published somewhen 1937 in the Rhodesian Herald. I received a copy of the original manuscript which is presented below. The route is reconstruced to my best knowledge. I tried to find as much contemporary information as possible ,especially about the airports used at that time. If you click on the links, there is some contemporary information about the airports, as they were available to the pilots then, derived from the International Flight Handbook, 1931, Imprimerie Crété S.A., Paris.

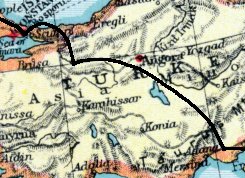

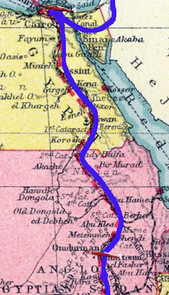

As you might notice, Hallam Elton followed the air route established by Imperial Airways from Alexandria onwards. By taking the route via the Balkans in Europe, he avoided the large overwater-portions of the Imperial-network.

Now that I glance back from an aerial voyage from England to Rhodesia, I discover my way defined by numerous incidents – a wake glistening with touches of humour and rare beauty, that prompts me to fly the course again, accompanied by less fortunate readers.

Having landed at Lympne to be “cleared” from England, I found numbers of noisy light planes jostling one another in and out of the airport, and I was informed that a “free weekend” was occurring at Le Touquet. I was obviously supposed to know what this meant, so rather than risk my status as one of the “chaps”, I nodded knowingly. But judging from my small knowledge of the Englishmen, the event must have had something to do with the free distribution of beer to cause the serious enthusiasm shown.

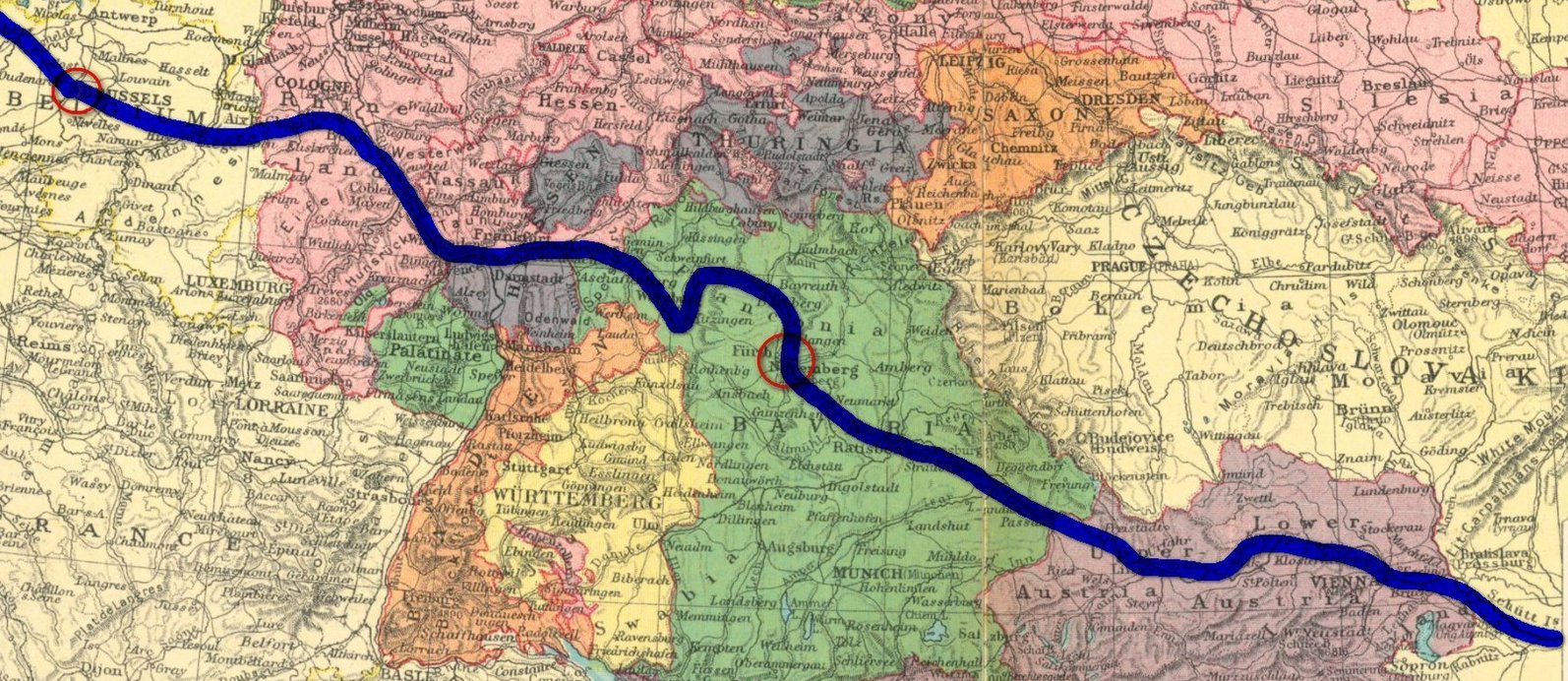

Then over the Channel to Brussels,

where my journey nearly ended. As I touched down, the jamming of my starboard brake whizzed me round in two tight circles on one wheel.

It was next discovered that a most important paper was missing from my great pile of permits and log books. After fruitless search, and passing with increasing dejection to offices of higher and higher officials for over an hour, and being told that I should have to remain for three days while they got in touch with the British Air Ministry, the affair seemed to be taking on an air of international crisis, and I was feeling like the very worst type of felon, when I suddenly discovered the document in the hand of the first official to whom I had entrusted my papers. I could have cried!

After that, I lost no time in leaving. Soon, the flat, open country of France and Belgium changed to the pleasant hills and forests of Germany with the buildings clustered under slate roofs: whilst through it all ran the ribbons of utterly straight road, Hitler’s work: they will move civilians or troops swiftly.

I found the Germans to be delightful people, and all their officials appeared to be very young. As a whole, the nation seems passionately to love uniforms and badges; the latter strewed the lapel of almost every civilian’s coat.

I noticed about these people the vital alertness of a people awakening from a nightmare. Occasionally, a group of girls or boys in uniform would pass by, singing patriotic songs. On every side, the repression of an humiliated nation is passing away to the healing sound of song and military planes: I wondered whether it would lead to over-compensation, in the psychological sense!

The variety of clothing worn about town was startling – at the same time it was refreshing to see every man expressing himself as he felt inclined: there were the orthodox city suits topped off with a skull cap, coloured plus-fours with white stockings, and “glad-necked” shirts, while the very fat men seemed unable to resist an Alpine costume of embroidered waistcoat and buckskin shorts. I learned that the shorts cannot be washed, but are sent to the dry cleaners about twice a year!

East of Nuremberg, the sombre slate roofs of the villages at length changed to cheerful looking tiles near the Austrian border. And now I was over the great Danube river, and need not worry about navigation

– I sat back and chewed a very expensive stick of biltong bought, cellophane wrapping and all, in London before departure. And so to Vienna, on down the Danube to Czechoslovakia, and out again into Hungary, where I alighted at Budapest.

I had heard that here were the most beautiful women in the world. But I was distinctly surprised to find that the Budapest women on the whole were the most fascinating that I had seen; the very attractive ones held themselves well, walked well, and found paint and lipstick unnecessary, which was very refreshing. And above all, they looked extremely intelligent.

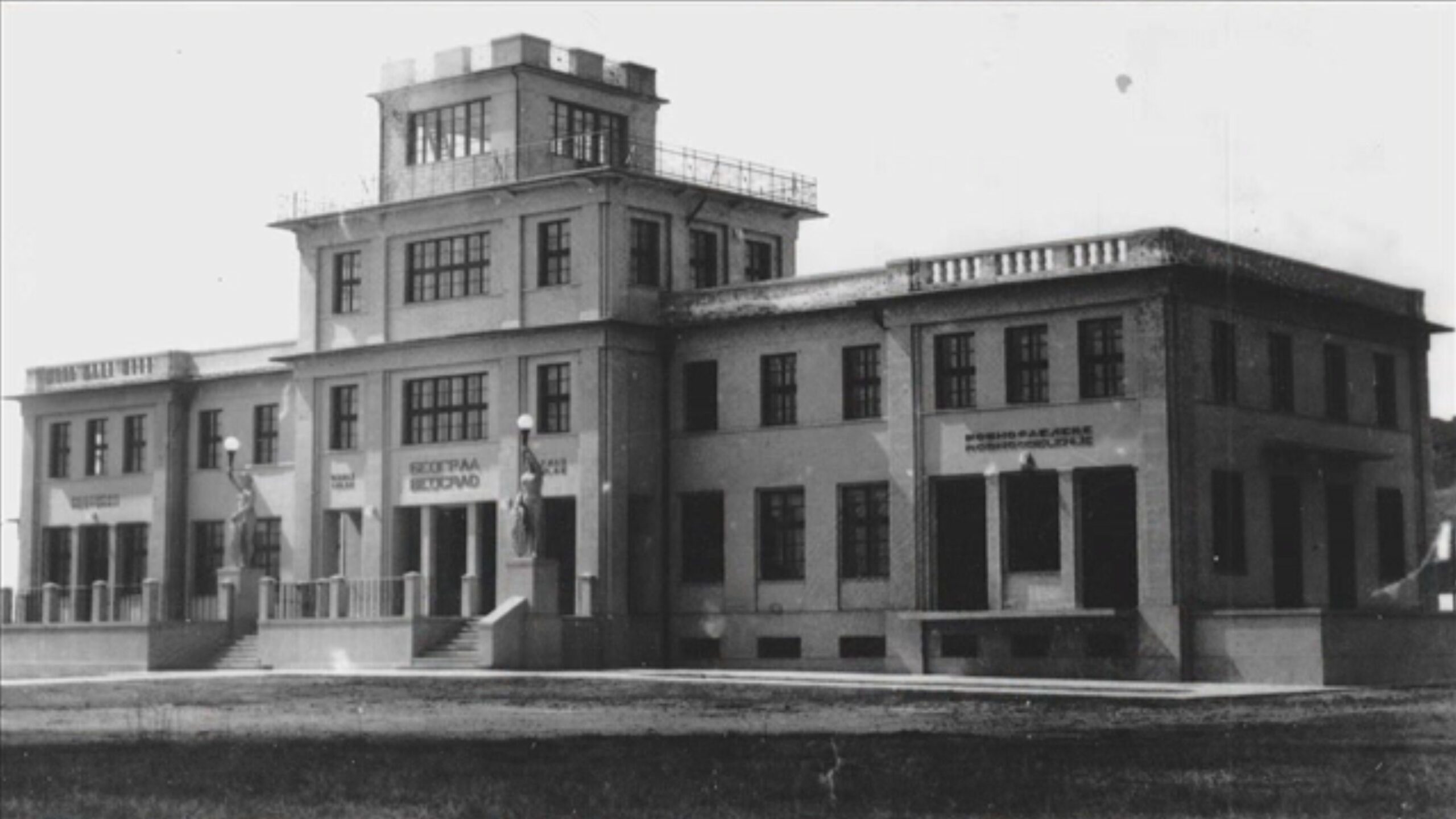

I reached Belgrade tired, and thankful for the night. In the hotels here, as anywhere east of Belgium, there is no soap, visitors are expected to bring their own. The country seems very poor, and the roads are dreadful. I believed that I had at last discovered where all the used-up cars of the world go – British, French, American and German I saw, and there was a homely and honest touch about them.

Pieces of wire played no mean part in their maintainance; none of your purring, sparkling creations, often never paid for! I was amazed to see the energy being expended here in the training of military pilots. I heard them flying throughout the night – it is tragic, as the people need the money so badly.

I left in my Heinkel for Bulgaria on a lovely sunny morning.

At Sofia – being determined not to miss a national dish – I lunched off great hunks of bread with cream cheese and a bowl of curds – first wrestling with a piece of soap and some water for ten minutes with not the slightest sign of a lather.

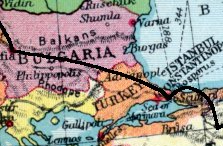

Having by now developed some obscure oil trouble in the engine, I realised that I could not reach Instamboul [Constantinople] in one hop, and sounded an official on the subject. I asked him whether I might land somewhere to re-oil; he informed me that on no account was I to land before Instamboul. “But”, I persisted, “if I have to come down because the machine will not stay in the air any longer?” “Then you must also on no condition land.”, he assured me sternly. “Do you not see that the next call on your papers is Instamboul?”

After several hours across flat country, my oil gauge registered zero. I found a strip of even-looking ground along a river bank, far from any village or sign of authority, and landed among a herd of surprised white cows – all of these Bulgar animals are pure white, and very attractive against their green pasture.

In a few minutes, a hundred dazed-looking peasants were gathered about me, staring in a bovine manner. I had a feeling that perhaps in about half an hour’s time, they might register surprise suddenly, as their reflexes worked. But I must not be unkind: I must have appeared a fully qualified lunatic as I hurled myself onto the spare oil tin – bunged the oil into the tank – started my engine – and bundled into the cockpit, gazing fearfully over my shoulder for signs of the police; had any arrived on the scene, I might have been detained for weeks. After managing, with much frantic waving, to get both the cows and the peasants out of my path, I roared thankfully away – clearing some tall trees with an upward leap, thanks to the Heinkel’s automatic wing flaps. These little countries are simply surrounded by fortified areas, through which one must thread one’s way carefully, and only where approved – flying low enough for your registration letters to be read – smiling amicably right and left, for this military stuff is frightfully serious. At that moment – unknown to me – my friend, Guy Valentine, was a prisoner in Italian Libya, living on bread and water, for daring to land near a motor lorry in an entirely featureless desert, to ask the way. I understand that Mussolini‘s braves were convinced that the pitot-head of Guy’s air speed indicator was a new machine-gun of a hideous type!

I was now in Turkey, and had the unpleasant experience of having to fly forhalf an hour, ten miles out over the seas, of Marmara, with my dial showing no oil – this was, of course, by reason of fortifications. My state of mind was exaggerated by tummy-ache – a Bulgarian curds kind of ache.

Eight thousand feet below, I saw the sunlight glinting on a shoal of fish – I threw them a meat pie about which I had serious misgivings. I suddenly found myself in one of those cleaning moods that one gets at home; I jettisoned two stale sandwiches, a sucked sweet off the seat of my pants, and then polished my instruments until I could cut my engine and go in from the sea, down in one long glide to the pink tiles of Instamboul.

The place looked very lovely in the late sunlight, with its beautiful surrounding of yinted waters and purpling hills. I hope to return one day.

A very pleasant little Tukish officer with bright brown eyes took charge of me. He wished to know – rather disparagingly – whether I spoke nothing but English. I informed him loftily that I could converse in Mxosa, Afrikaans, Chikaranga and Wasahili. He appeared dumbfounded, addressed me with added respect, and invited me to take beer with him – the Turks make good, potent beer. We walked some distance to an hotel, while a soldier carried my baggage – they treat their lower orders with less respect than we treat our natives.

The terrace of this place hung over the incredibly clear water of Marmora – may I never forget that picture. Except for the quiet lap of shore water, the sea was hushed and mirror like, vivid blue viewing with gorgeous pinks which must have fallen from a hidden sunset, an exquisite Turner painting of rainbow mistiness, out of which appeared nebulously the purple shapes of the distant islands of Kidzel and Adalar.

From Instamboul, ubiquitous forbidden areas forced me to fly over northern mountains to the Black Sea before turning south-east for Eskishehr, where a Captain Sharif, a charming man, trained at the British Central Flying School, was in turn instructing Turkish pilots in Turkish made military biplanes, and the way those lads were throwing them about in the sky would open the eyes of many a Western nation.

Eastwards, the country was now becoming flat, barren and hot. I made for the Taurus Mountains, but found them rising to an immense height into solid cloud. However, I managed to get through where the railway runs. This is a wonderful feat of engineering: the trains make their way through gigantic cracks in the massive rock, thousands of feet deep, and so sheer that whereas there appeared to be just room for the tracks below, I felt that my wingtips, on many occasions, were almost brushing the walls some thousand feet above. I found the vicious gusts in these constricted passages very frightening.

On the far side I refuelled at Adana in Cilicia, and hurried in the late afternoon across the Gulf of Alexandretta, to climb with difficulty through the gathering clouds over the Jawur Mountains and shoot away down the other side, across the great barren spaces of French Syria to rest at Alleppo in the dusk.

In the early morning, I went on over the same kind of barren brown surface to alight at Damascus. for engine oil. The French delayed me for a long while asking futile questions over and over again – all my papers had been put in order by themselves at Aleppo. In the middle of this interrogation, a military plane of theirs gracefully stood on end in the centre of the aerodrome. All offices emptied as a gestulating mob surged across in the wake of an ambulance. However, I got away just before going crazy.

I was ushered into the Holy Land by scarlet blooms in the bottom of erosion gullies. Another moment and the sight of a glistening sapphire filled me with emotions – the Sea of Gallilee! I swooped down eight hundred feet below sea level, passing a few feet over the place of the loaves and Fishes. At the surface, the water turned to pale green, and weed was visible below. l flew over the length of Galilee some six feet from the water, struggling to realise that this was where the Christ walked and sheet his happiest years: that down these precipitous slopes on my left the Gaderene swine rushed: from this bank at dawn He hailed the fishermen after the Crucification. Thinking that I should never again fly this distance below sea level, I throttled my engine well back, and had the surprising experience of floating alone as though I were riding a feather, whereas at sea level, the machine would have dropped at once.

Jerusalem was unfortunately hidden by a bank of cloud. But Nablus, Samaria, Tiberius and blessed Nazereth were there – clusters of flat – roofed houses, from among which occasionally sprung the spire of some devoted belief, looking rather embarrassed at its enterprise in height and shape. Far ahead could be discerned the black shapes of the vast citrus orchards round Jaffa, against a background of very solid blue Mediterranean fringed with a white line of surf. This Palestine, apart from small settled spots, appears to be a cruel, burned-up, barren, waterless and treeless land: a land to breed ruthless children to whom “force” is the law.

Crossing the Sinai desert and the Suez Canal. I glided thankfully down to rest at Almanza aerodrome (most probably Al Manzila or Manzala, the administrator), on the edge of the desert stretching southwards – “twixt the desert and the sown”. Here I remained at the clubhouse while Misr-Airwork removed my trusty engine to discover the oil trouble. Whisky is six shillings a bottle!

I have never before seen quite such scarlet-fleshed water melons as in Cairo. The vendor will walk the streets with the fruit balanced miraculously upon his head; as each slice is sold, thousands of rejoicing flies pack into the opening – but who cares?! What happens to the purchaser is the will of Allah!

I was intrigued by the clever netting placed everywhere over windows to keep out flies; it is made of light string which the insects mistake for spider web. I have not once seen a fly pass through: we might well emulate it in this country, as the slightest breeze comes through the wide mesh.

Onward over the desert – the real stuff – sand, and nothing but rolling sand, and so Khartoum aerodrome in the late afternoon.

After a bath, and how glorious it was, i spent a cheery and irresponsible evening as guest of the R.A,F. squadron stationed there. I gathered, from their chatter, that they were bitterly disappointed at not being next on the list for a flight south to Salisbury. At dusk, the Imperial Airways liner roared in, with lights blazing, a fine sight.

Rain had fallen in the Sudan, and at length a green patch appeared on the tawney desert, and then at last, wonder of wonders, a green rolling expanse, real refreshing grass, the first since leaving Bulgaria, 2.700 miles back!

I emerged from a rainstorm to find the little landing ground of Malakal, on the border of Abyssinia. and upon it, to my surprise, there rested no fewer than three planes! One was the Imperial airways machine. one was the Puss Moth of my friend Guy Valentine, who had at length got away from the Italians, and the other was a Wright – Whirlwind Fokker biplane, piloted by a young Swiss still searching for some of his countrymen lost with the ambulance unit during the campaign.

Valentine and l left within a few minutes of each other, and greatly enjoyed watching the herds of big game below. We put down at Juba for the night.

Valentine was delighted to discover a grass tick on his leg. We celebrated it, for we felt that we were as good as home.

The following morning we continued as usual, soon after each other, soon entering extensive and very bad weather with tropical rainstorms. Many gloomy thoughts entered my head, and I was delighted to have them banished by the sight of the Puss Moth already down when I arrived at Kisumu – a very good effort – as Valentine had few flying hours to his credit: in fact, I found later that he had a definite flair for finding his way about in and through the dirtiest weather.

Kisumu, where we alighted for lunch, is a most attractive place, full of delightful people. We left again, and I could see the sun glinting on Valentine‘s wings some miles away as we climbed to nine thousand feet to clear the high plateau north of Nairobi. Fine, indigenous timber covered these slopes, but the top was open country, gently undulating, with prosperous looking farms spread all over.

I chanced upon a mirror – like lake, very blue and very still, reflecting puffs of cumulus cloud, and margined by a broad zone of gorgeous rose-pink. The whole was embraced by a wide beach of sand, as clean and as white as that of Muizenberg. But I was puzzled by the pink, and glided down to explore. The colour became agitated, and I realised that it was hundreds of thousands of flamingoes – perhaps the most exquisite sight in my entire voyage.

At Nairobi, I learned that my flamingo lake was named Nakuru.

From Nairobi, we made for Kilimanjaro and found that majestic mountain shrouded in sombre storm. But at thirteen thousand feet it burst from the darkness to soar for many more thousand feet into tropical sunlight, which beat upon the dazzling summit of snow.

I now took a keen personal interest in the country, which I had covered in very different circumstances during the last war: I was thrilled when passing over Kondoa – Irangi to spy the same fat, matronly baobab behind which I had rushed when under shell-fire.

Onwards all day over dreary bush to Broken Hill: then early the following morning we were headed for Salisbury – nearly home! And now at last, Salisbury – a brief refuelling and off to Umtali.

How delightful it was to be home! I burst into song – I often do when I am flying, as I cannot hear myself.

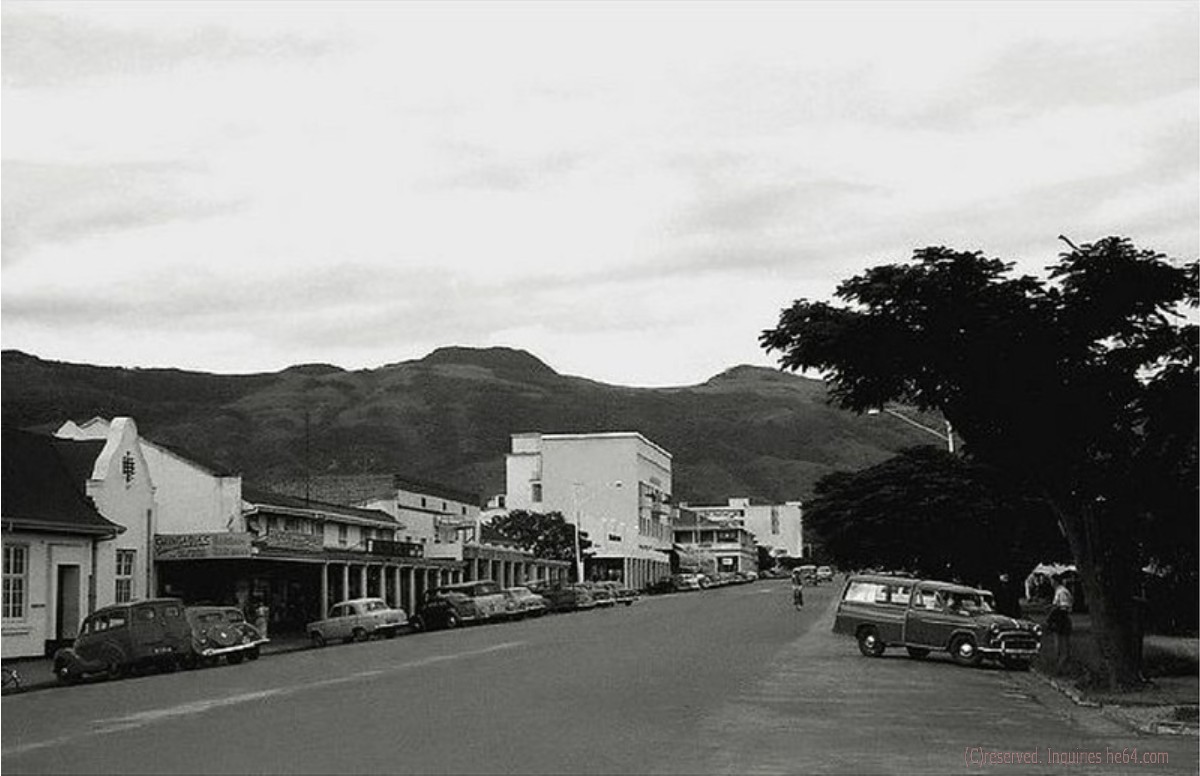

I put the Heinkel down in her own peculiar and spectacular way before an ` embarrassingly large crowd of good Umtali friends, and I reluctantly handed my good ship over to her new owner, Chris Perrem.

In every country through which I passed I found men, like ourselves, cheerful, friendly, with a good sense of right and wrong, delighting in humour, pleased to help, with all the little family worries of life creasing their faces, and worshipping the same God. Can all these people be the puppets of unscrupulous leaders?

It is pathetic; they are all re – arming whilst peering fearfully over their shoulders at their neighbours – a lot of terrified children. And the more pugnacious they appear, the more frightened are they. If they could know each other, war could not be. Nowhere else in my travels did I find the tiny garden – a riot of flowers. that inevitably adorns the poorest cottage in England.